What is Hypomagnesemic Tetany or Lactation Tetany? Definition and Etiology

Hypomagnesemic tetany (also called Lactation Tetany, Grass Tetany, or Grass Staggers) is a serious metabolic disease in cows. This disease is caused by a deficiency of magnesium in the blood (hypomagnesemia), identified by serum magnesium levels falling below 1.2 mg/dl.

The key characteristics of this disease include extreme excitability, muscle spasms (tetany), convulsions, respiratory distress, collapse, and ultimately, the death of the cow if not treated in time.

This disease is primarily seen in the winter season. The reason is that the green grass growing in winter has low magnesium content. When animals consume this grass in large quantities, the magnesium level in their blood decreases. This is why this disease is also called Winter Tetany or Grass Tetany.

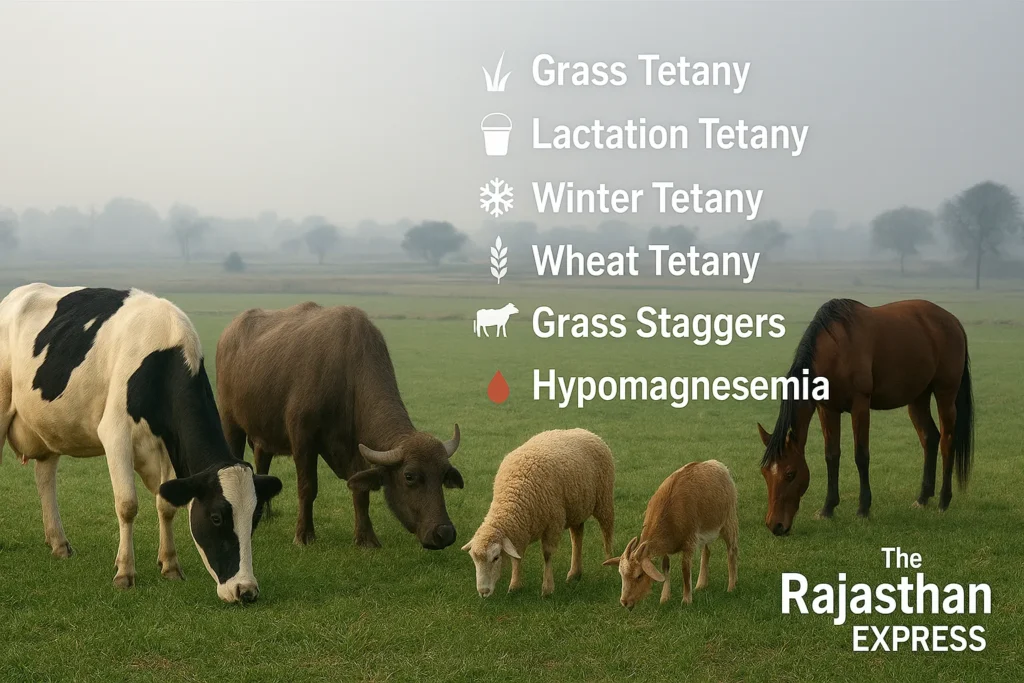

Hypomagnesemic tetany is found in animals like cows, buffaloes, sheep, goats, and mares. However, in cows, this disease is caused by a magnesium deficiency, while in mares, lactation tetany is mainly due to a calcium deficiency.

This disease can also occur in 2 to 4-month-old calves that are fed only milk. This happens because magnesium absorption drops from 87% at 2-3 weeks of age to just 32% at 7-8 weeks of age. All metabolic diseases are non-infectious, meaning they do not spread from one animal to another.

Grass Tetany (Hypomagnesemic Tetany)

| Synonyms / Other Names | Grass Tetany, Lactation Tetany, Winter Tetany, Grass Staggers, Wheat Pasture Poisoning, Milk Tetany, Calf Tetany, Hypomagnesemia |

|---|---|

| Definition | A potentially fatal metabolic disorder in ruminants caused by hypomagnesemia (serum Mg <1.2 mg/dL) leading to neuromuscular hyperexcitability, convulsions, collapse, and death if untreated. Often associated with hypocalcemia and imbalances in phosphorus. |

| Etiology & Pathophysiology |

|

| Predisposing Factors |

|

| Clinical Signs |

|

| Diagnosis |

|

| Critical Mineral Ratios |

|

| Treatment |

|

| Prevention & Management |

|

| Prognosis | Guarded to poor if untreated. Acute cases may be fatal within hours. Chronic latent magnesium deficiency (CLMD) may result in hidden production losses and subclinical health issues. Recovery is slower than hypocalcemia due to delayed Mg normalization in CSF. |

| Species Affected | Cattle, buffaloes, sheep, goats; mares (lactation tetany due to Ca deficiency); calves 2–4 months fed only milk |

| Advanced Notes |

|

| Sources: Merck Veterinary Manual; University Extension Services; USDA; FAO; Government Agricultural Research Reports; PubMed;The Rajasthan Express | |

Metabolic Disease in Animals: Definition, Types, and Key Characteristics

Definition:

Metabolic Diseases are those diseases which occur due to deficiency, imbalance of nutrients, or disturbance of metabolism in the body. These diseases are especially related to milk production, pregnancy, and the energy requirements of the body.

Read More About : Metabolic Disease

Main Features of Metabolic Disease in Dairy Cattle

- These diseases are Non-Contagious — do not spread from one animal to another.

- In most cases, these diseases are related to the production system, hence they are also called Production Diseases.

- Especially pregnant and milk-producing animals (like cow and buffalo) are more susceptible to these diseases.

- The possibility of metabolic diseases increases with increasing milk production.

- In native cows (Zebu cattle), the highest possibility of metabolic disease is found in the third calving.

- In exotic cows (Exotic Cattle), this possibility is highest in the fifth calving.

- In buffaloes, the possibility of metabolic diseases is mostly in the fourth calving.

- The order of possibility of metabolic diseases is as follows:

Exotic Cow > Native Cow > Buffalo - The possibility of Downer Cow Syndrome, Ketosis, Postpartum Haemoglobinuria, and Mastitis disease is higher in exotic cows, especially in the Holstein-Friesian breed.

- These same diseases are found mostly in the Sahiwal breed in native cows.

- The possibility of Milk Fever is highest in Jersey cows.

We have also explained these diseases in detail.

Explore the key metabolic diseases in cattle with quick links to each section:

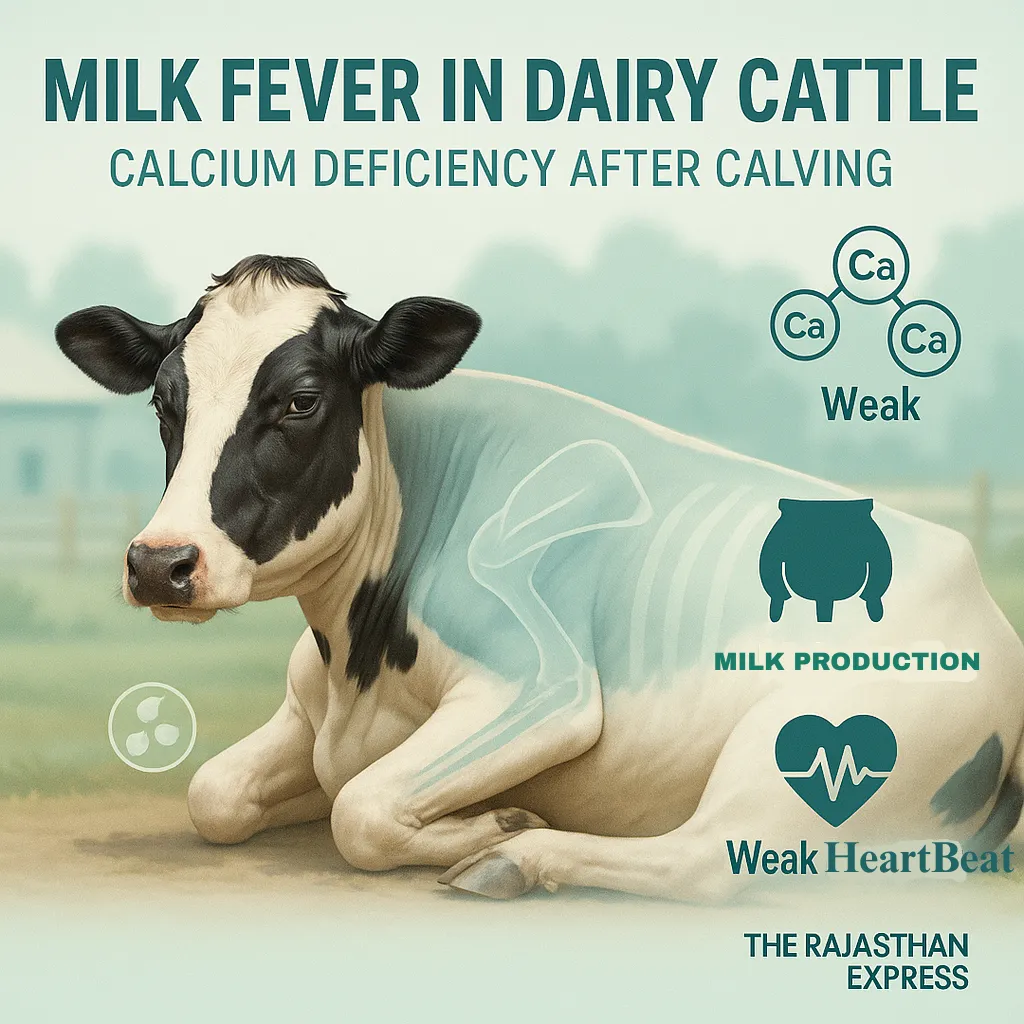

- Milk Fever – Calcium deficiency immediately after calving

- Downer Cow Syndrome – Complications from prolonged lying after milk fever

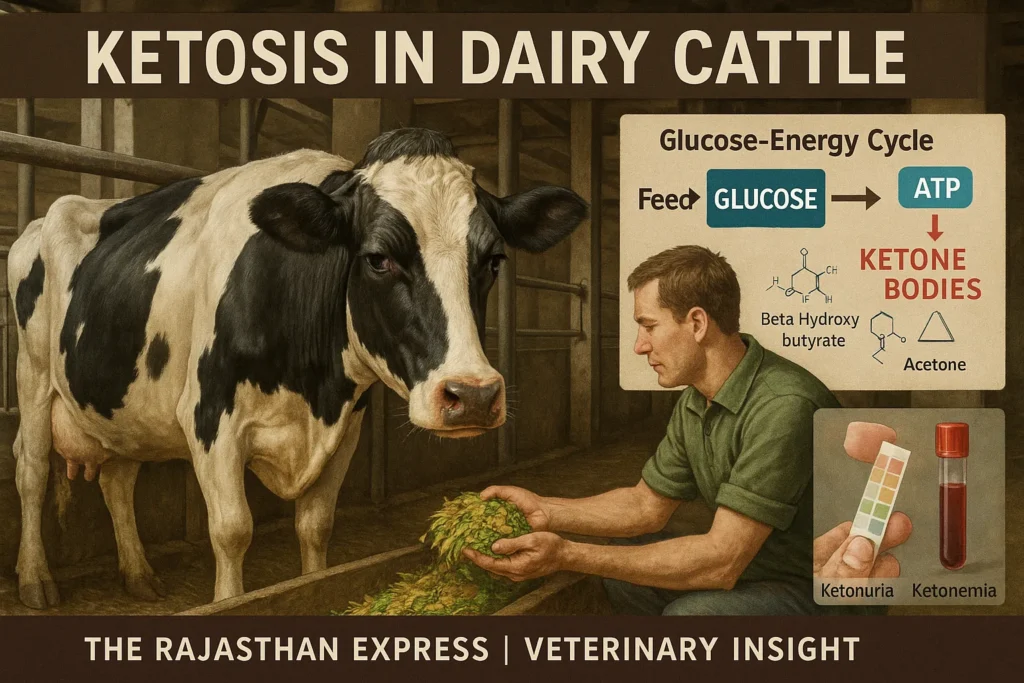

- Ketosis In Cattle – Energy deficiency and ketone accumulation

- Postparturient Haemoglobinuria – Red blood cell destruction due to phosphorus deficiency

- Grass Tetany – Muscle cramps from magnesium deficiency

- Pregnancy Toxemia – Energy deficiency in late pregnancy

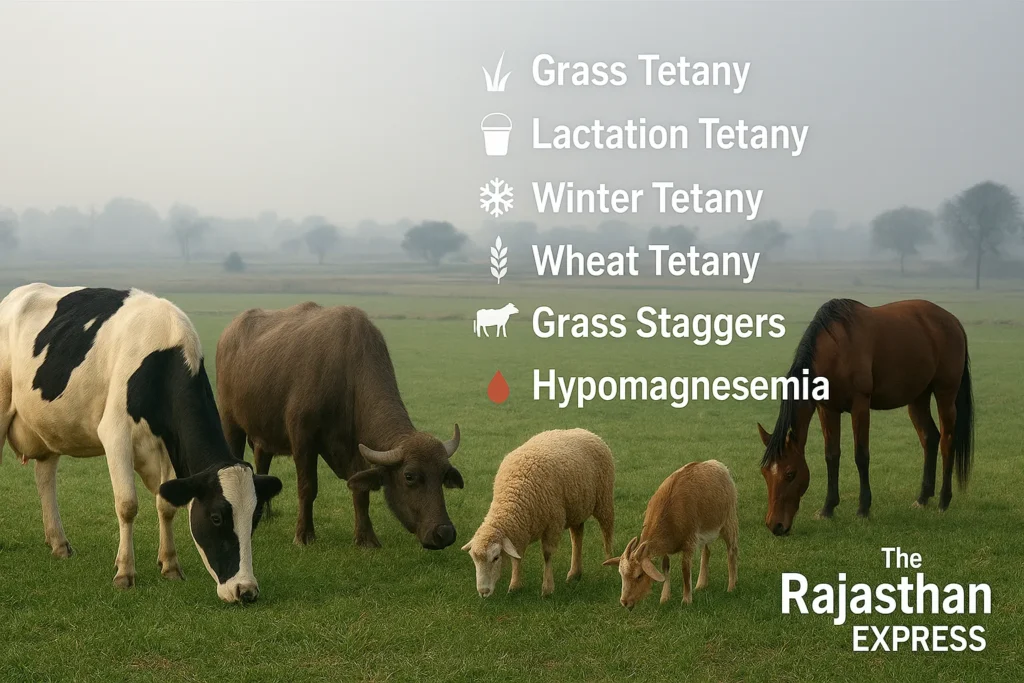

Hypomagnesemic Tetany: Synonyms and Types

Hypomagnesemic tetany is a fatal metabolic disease caused by low levels of magnesium in the blood. Based on its symptoms and the specific circumstances under which it occurs, it is known by several different names.

Grass Tetany and Other Common Synonyms

Hypomagnesemic tetany is known by names such as Grass Tetany, Lactation Tetany, Winter Tetany, Wheat Posture Disease, and Grass Staggers.

- Grass Tetany: This name is prevalent because the disease is often seen in animals grazing on green forage (grass).

- Lactation Tetany: This name reflects its tendency to occur in high milk-producing (lactating) cows and buffaloes, as significant magnesium is excreted through milk.

- Winter Tetany: This indicates its increased incidence during the winter season.

- Wheat Tetany: This name is specifically associated with outbreaks in pastures grazed with wheat.

- Hypomagnesemia: This is the technical term indicating the root cause of the disease, i.e., low blood magnesium.

Primary Types and Causes of Grass Tetany Disease in Cattle

Hypomagnesemic tetany can be classified based on primary causes and the affected animal group. This classification aids in the prevention and treatment of the disease.

| Primary Types and Causes of Grass Tetany Disease in Cattle | ||

| Type | Affected Animals | Key Cause and Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Grass Tetany | Adult cows, buffaloes (mainly dairy) |

Cause: Feeding rapidly growing green grass (e.g., ryegrass, wheat pasture) with low magnesium. Mechanism: Such grass often has high potassium (K) and nitrogen (N), which impede magnesium (Mg) absorption (nutrient imbalance). |

| Winter Tetany | Adult ruminants |

Cause: In winter, grass growth slows, reducing Mg content. Mechanism: Animals rely more on dry fodder, a poor Mg source. Cold stress also raises Mg demand due to increased metabolic rate. |

| Milk Tetany / Calf Tetany | 2–4 month old calves |

Cause: Reliance solely on milk (often Mg-deficient). Mechanism: Milk is low in Mg, and absorption in young calves is inefficient due to immature digestion → complete dietary Mg deficiency. |

| Lactational Tetany | High milk-producing mares (mainly) and cows |

Cause: Excess Mg and Ca loss via milk. Mechanism: At peak lactation, Mg loss through milk may exceed intake → negative balance. Feeding low-Mg, high-K forage increases risk. |

| Grass Tetany is primarily a magnesium imbalance disorder linked to diet, season, and lactation. | ||

The Root Cause of Grass Tetany: Soil-Plant-Animal Interrelationship

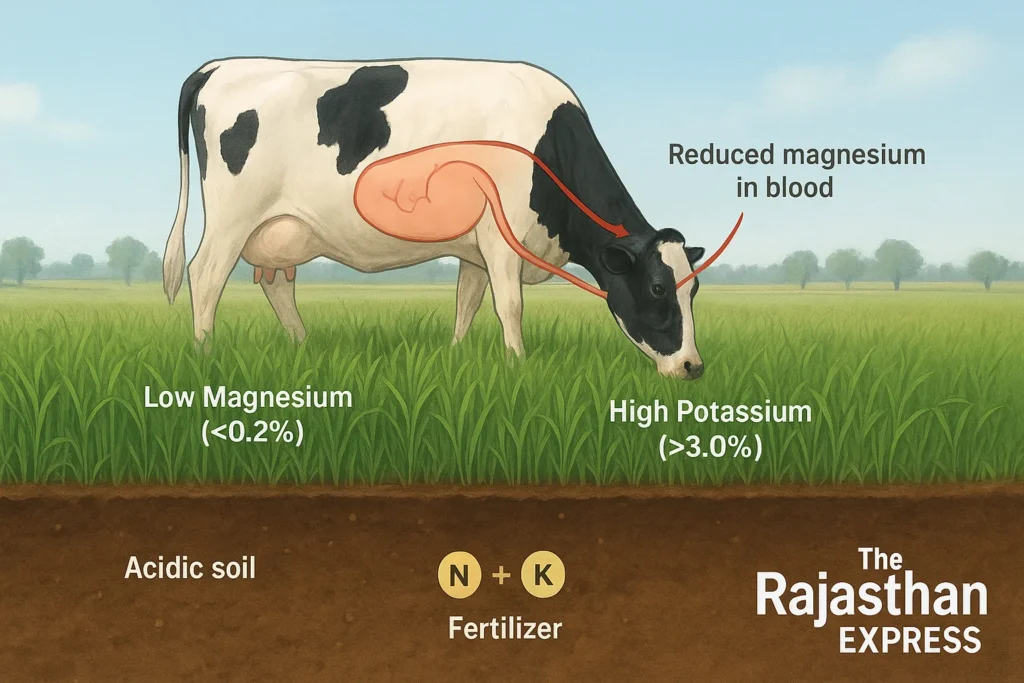

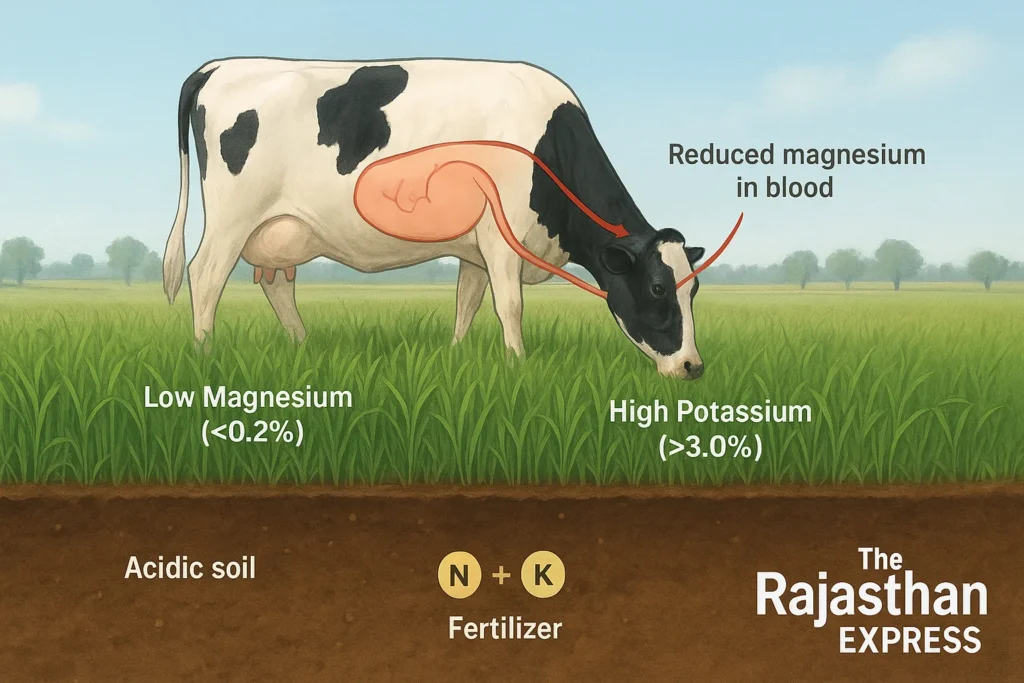

Hypomagnesemic tetany is not just an animal disease; it is a soil-plant-animal metabolic disorder. Its root cause is often hidden in the soil itself.

- Soil Factors: Acidic soil, high potassium (K) levels, and excessive use of nitrogen fertilizers reduce the availability of magnesium from the soil.

- Plant Factors: Fodder (e.g., ryegrass, wheat) growing in such soil has very low magnesium content (< 0.2%) and very high potassium content (> 3.0%).

- Animal Factors: When animals eat this imbalanced fodder, the absorption of magnesium in their stomach is further reduced, leading to a deficiency in the blood and the appearance of tetany symptoms.

Predisposing Factors for Grass Tetany

Predisposing factors for this disease include:

- Poor weather conditions.

- Starvation.

- Long-distance animal transport.

- Grazing on pastures with young grass containing less than 0.2% magnesium on a dry matter (DM) basis.

- Fodder from crops where urea and potash fertilizer have been used heavily may be deficient in Mg.

- After calving, calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), and magnesium (Mg) are excreted from the body with milk, increasing the risk of hypomagnesemic tetany in dairy animals.

👉 Magnesium absorption is best at a Na:K ratio of 5:1. If this ratio falls below 3:1, absorption is impaired.

Normal Blood Parameters and Risk Levels

Normally, the blood Mg level in the body is 2.2 – 2.7 mg/dl. Falling below this indicates a magnesium deficiency. The normal calcium-to-phosphorus ratio in a cow’s body is 2:1.

The normal levels of minerals in the blood of various animals are given in the following table:

| Normal Blood Parameters and Risk Levels in Different Species | ||||||

| Parameter | Units | Cattle | Buffalo | Sheep | Goat | Horse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | mg/dL | 8–12 | 8–14 | 11–13 | 9–12 | 10–13 |

| Phosphorus | mg/dL | 4–8 | 6–10 | 5–7 | 4–10 | 1–5 |

| Magnesium | mg/dL | 1–3 | 2–4 | 2–3 | 3–4 | 1–2 |

| Maintaining mineral balance is critical for preventing metabolic disorders in livestock. | ||||||

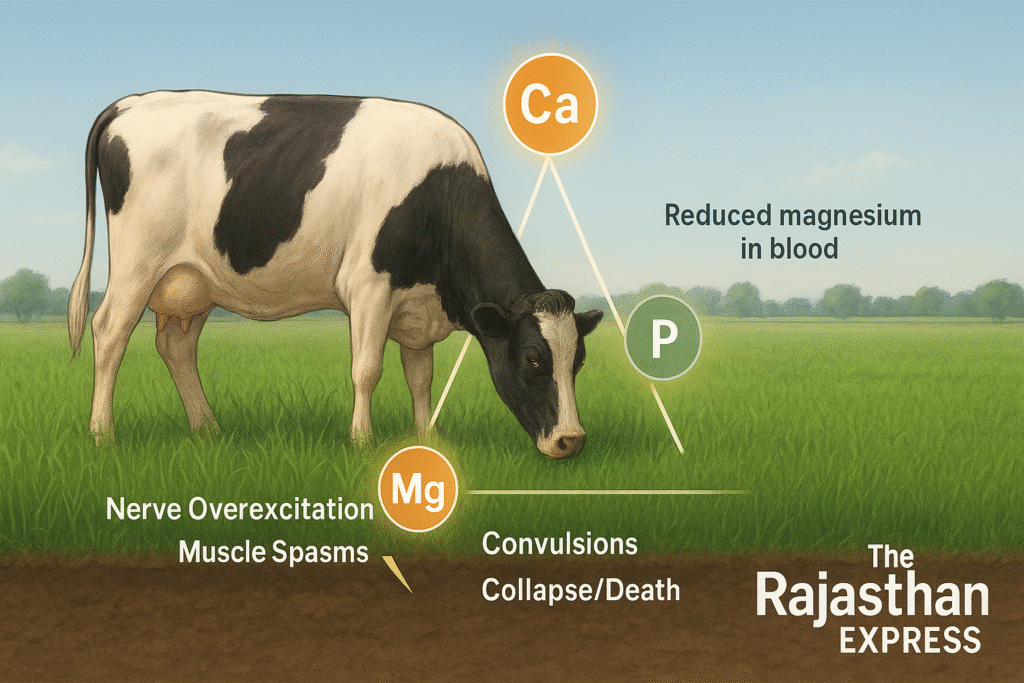

Pathogenesis: How Hypomagnesemia Causes Tetany in Cattle

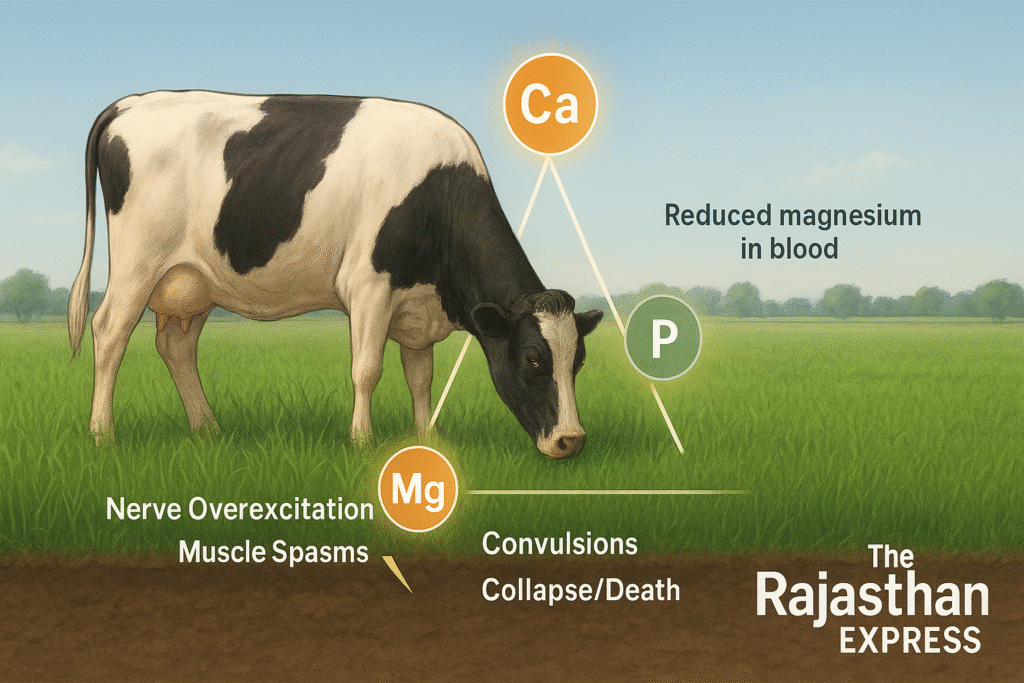

Calcium-Magnesium-Phosphorus Equilibrium and Neuromuscular Effects

1. Introduction to Electrolyte Imbalance in Ruminants

The balance between calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and phosphorus (P) in the blood of ruminant animals is a fundamental aspect of their metabolic health, directly affecting their productivity and well-being. When this delicate balance is disrupted, animals fall prey to metabolic diseases such as Milk fever (hypocalcemia), Downer Cow Syndrome , Postpartum Hemoglobinuria (hypophosphatemia), and hypomagnesemic tetany.

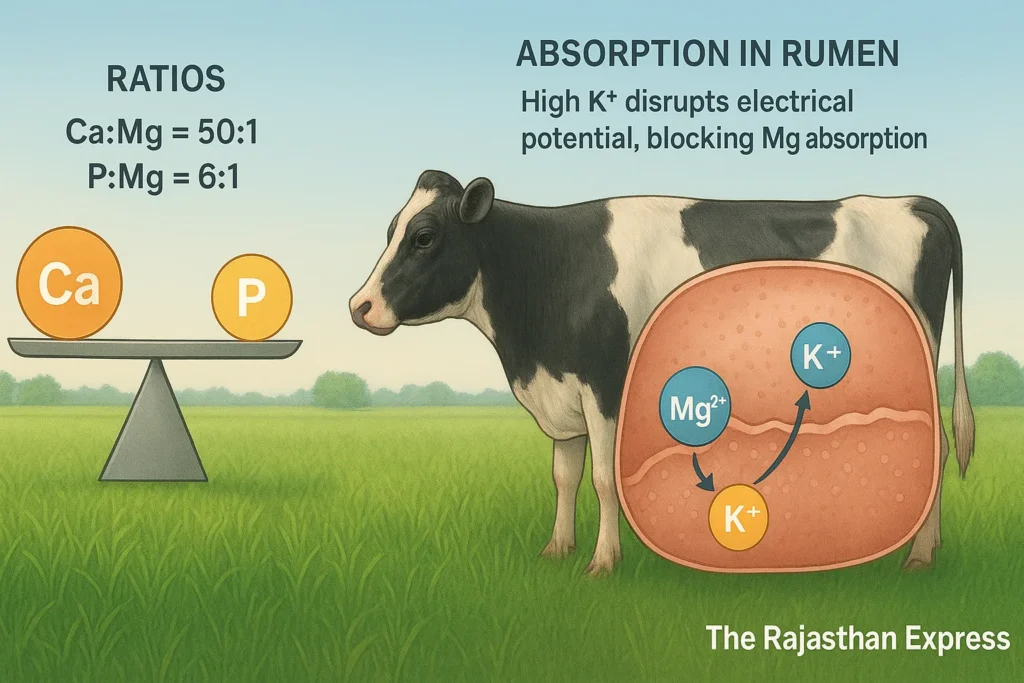

2. The Critical Role of Calcium, Magnesium, and Phosphorus Ratios in Cattle Health

Why Mineral Ratios are Crucial for Metabolic Health

Maintaining a specific ratio of Ca, Mg, and P in an animal’s blood is extremely important for healthy metabolism. The ratios are as follows:

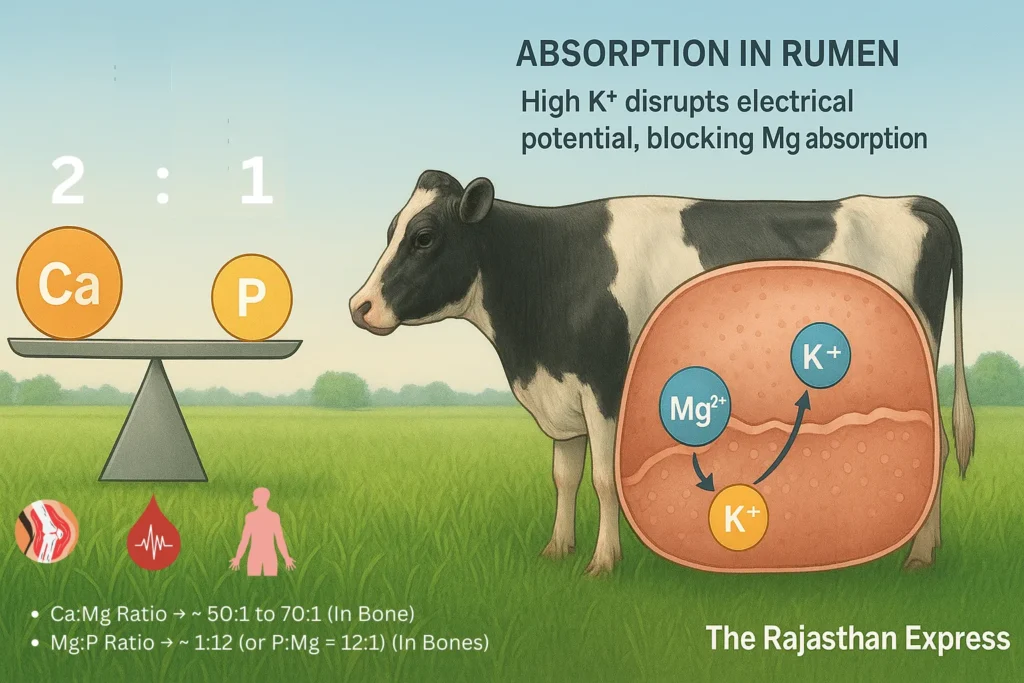

A). Mineral Ratios in Bone: The Structural Reservoir

Bones act as the body’s mineral bank. They store approximately 99% of Calcium (Ca), 85% of Phosphorus (P), and 60% of Magnesium (Mg). These minerals are instrumental in building the skeletal structure.

An animal’s total body weight consists of approximately 3% minerals, 8% blood, 5% plasma, and 60–65% water.

- Ca:Mg Ratio → Approximately 50:1 to 70:1

- Why: Bone is primarily composed of a calcium-phosphate matrix. Bone ash contains about 36–39% calcium and only 0.5–0.7% magnesium.

- Ca:P Ratio → Approximately 2:1

- Why: This ratio is fundamental to hydroxyapatite crystals (the main mineral compound in bone) and remains stable.

- Mg:P Ratio → Approximately 1:12 (or P:Mg = 12:1)

- Why: The quantity of phosphorus in bones is far greater than that of magnesium.

B). Mineral Ratios in Blood Serum/Plasma: The Metabolic Activity Zone

Mineral levels in the blood are very tightly regulated. This compartment represents the immediately available and metabolically active mineral pool. Blood mineral ratios are used to detect their deficiency or excess.

Normal Blood Levels:

- Calcium: 8.5 – 10.5 mg/dL

- Phosphorus (Inorganic P): 4.5 – 8.5 mg/dL

- Magnesium: 1.8 – 2.6 mg/dL

Mathematical Ratios:

- Ca:Mg → Approximately 4:1 (e.g., 10 ÷ 2.5 = 4)

- Ca:P → Approximately 1.5:1 (e.g., 10 ÷ 6.5 ≈ 1.54)

- Mg:P → Approximately 1:3 (e.g., 2.5 ÷ 6.5 ≈ 0.38, i.e., 1:2.6)

⚠️ Critical Point:

The parathyroid hormone (PTH) maintains stable levels of calcium and phosphorus in the blood. If the blood magnesium level falls below 1.2 mg/dL, Grass Tetany (a fatal condition) can develop.

C). Mineral Ratios in the Whole Body: The Systemic Balance

This includes the average of all tissues—bone, muscle, soft tissue, and fluids. It represents the overall mineral balance of the entire system.

- Ca:Mg Ratio → Approximately 5:1 to 6:1

- Why: The ratio in bones is very large (~50:1), while it is smaller in soft tissues (~4:1). The average works out to 5–6:1.

- Ca:P Ratio → Approximately 2:1

- Why: This ratio is primarily influenced by the bones.

- Mg:P Ratio → Approximately 1:7

- Why: The amount of phosphorus is much higher than that of magnesium.

A Guide to Key Mineral Ratios

| A Guide to Key Mineral Ratios | ||||

| Compartment | Main Function | Ca:Mg Ratio | Ca:P Ratio | Mg:P Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | Storage & Structure | ~50:1 – 70:1 | ~2:1 | ~1:12 |

| Blood Serum | Metabolic Activity | ~4:1 | ~1.5:1 | ~1:3 |

| Whole Body | Total Balance | ~5:1 – 6:1 | ~2:1 | ~1:7 |

| Diet | Absorption & Health | 5:1 – 7:1 | ~2:1 | ~1:4 |

| Maintaining balanced Ca:Mg:P ratios is essential for skeletal strength, metabolic stability, and overall livestock health. | ||||

Key Takeaway: Dietary Intake vs. Bodily Structure

- The required Ca:Mg ratio in the diet should be approximately 7:1.

- When this ratio is correct, the absorption of both minerals is optimal.

- If the ratio becomes too large (e.g., 50:1), the absorption of magnesium is blocked, potentially leading to its deficiency.

- The body absorbs minerals from the diet in a 7:1 ratio and then distributes them to different parts to create structures—such as a 50:1 ratio in the bones.

3. Impaired Magnesium Absorption

Magnesium is absorbed in the animal’s stomach (rumen). Rapidly growing green grass often has two problems:

- Low Magnesium Content: They are naturally low in Mg.

- High Potassium Content: Such grass has very high potassium (K) content.

High potassium alters the electrical potential of the rumen wall (epithelium). This disrupts the specific transport mechanism responsible for magnesium absorption. As a result, the animal cannot absorb sufficient Mg, even if it is consuming Mg with the fodder.

4. Neuromuscular Effects and Symptoms

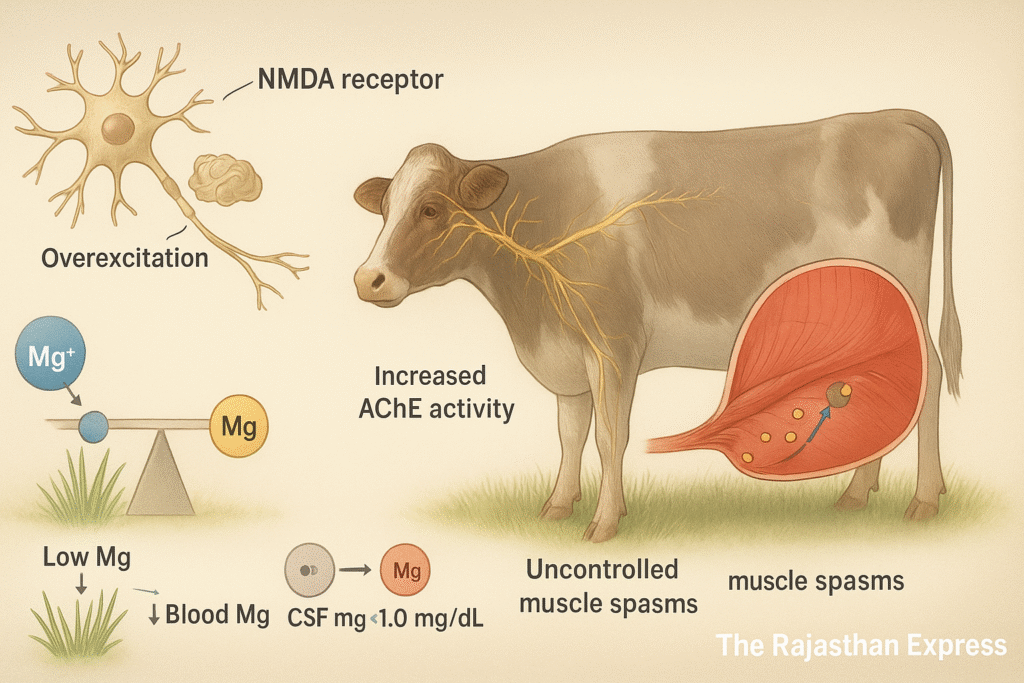

The pathogenic process begins when the magnesium level falls below a critical limit (serum Mg <1.2 mg/dL in cows). Magnesium acts as an essential cofactor for over 300 enzymatic reactions and is particularly crucial for proper nerve function. Magnesium works like a natural calming agent for our nervous system. Its deficiency causes nerves to become hyperactive.

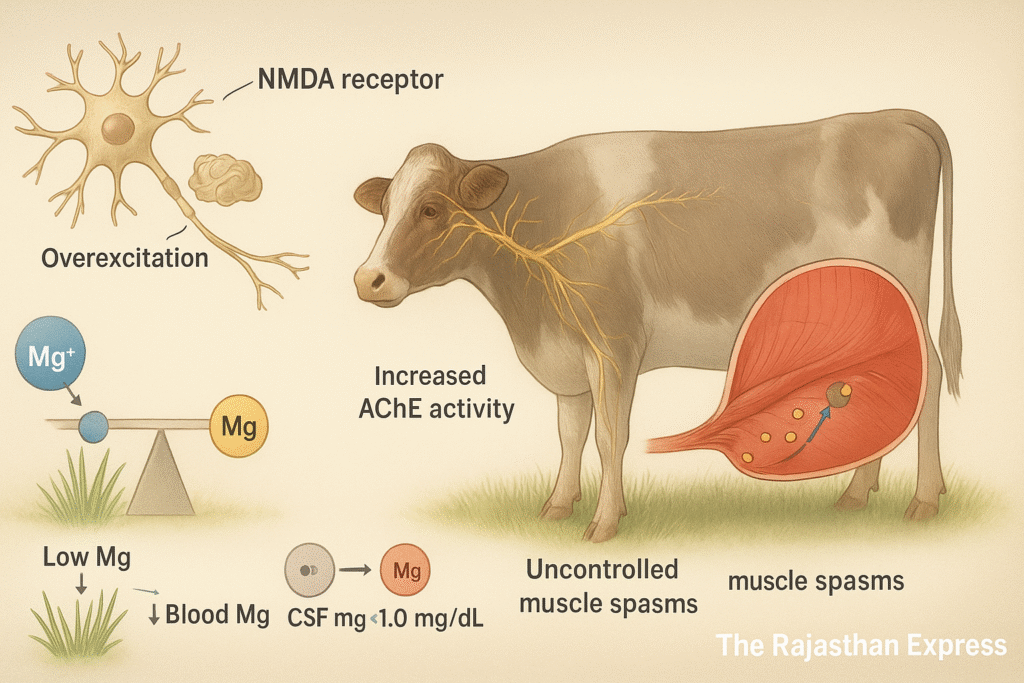

- NMDA Receptors: Mg acts as a natural “blocker” for NMDA receptors present in brain nerve cells. When Mg is deficient, this block is removed, leading to excessive excitation in nerve cells.

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): When the balance of calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), and magnesium (Mg) in the body is disrupted, it deeply affects nerves and muscles. Research indicates that in such conditions, the activity of an enzyme called acetylcholinesterase (AChE) increases. This enzyme breaks down acetylcholine, a chemical that signals muscles to move. The imbalance leads to garbled nerve signals and initiates excessive muscle activity or spasms, contributing to the signs of tetany.

5. The Significance of Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

Not only does the blood Mg level decrease, but the magnesium level in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) also drops significantly (<1.0 mg/dL). Since CSF directly surrounds the brain and spinal cord, its low level is directly responsible for nervous system dysfunction. This is why sometimes even a slight decrease in blood Mg levels can show severe symptoms in the animal.

Summary: Eating green grass → High Potassium, Low Mg → Mg absorption impaired → Blood Mg deficiency → Ca:Mg and P:Mg ratios deteriorate → Acetylcholinesterase enzyme becomes active and NMDA receptors become unblocked → Nerves become overly excited → Muscle spasms and symptoms of tetany appear.

Critical Mineral Limits and Ratios in Ruminant Blood

| Critical Mineral Limits and Ratios in Ruminant Blood | |||

| Parameter | Normal Value | Tetany Risk Value | Critical Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Magnesium (Mg) | 1.8–2.5 mg/dL | 1.2–1.8 mg/dL | <1.2 mg/dL |

| Serum Calcium (Ca) | 8–10 mg/dL | 7–8 mg/dL | <7.0 mg/dL |

| Serum Inorganic Phosphorus (P) | 4.5–8.5 mg/dL | — | — |

| Ca:Mg Ratio (in Blood) | ~4:1 to 5:1 | ~6:1 to 9:1 | >10:1 |

| P:Mg Ratio (in Blood) | ~3:1 to 4:1 | ~5:1 to 7:1 | >8:1 |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Magnesium | >1.0 mg/dL | 0.8–1.0 mg/dL | <0.8 mg/dL |

| Note: The ratios for dietary intake are different (Ca:Mg ~7:1). Blood serum ratios are calculated from actual blood levels (mg/dL). The ratios in bone are also different (Ca:Mg ~50:1). | |||

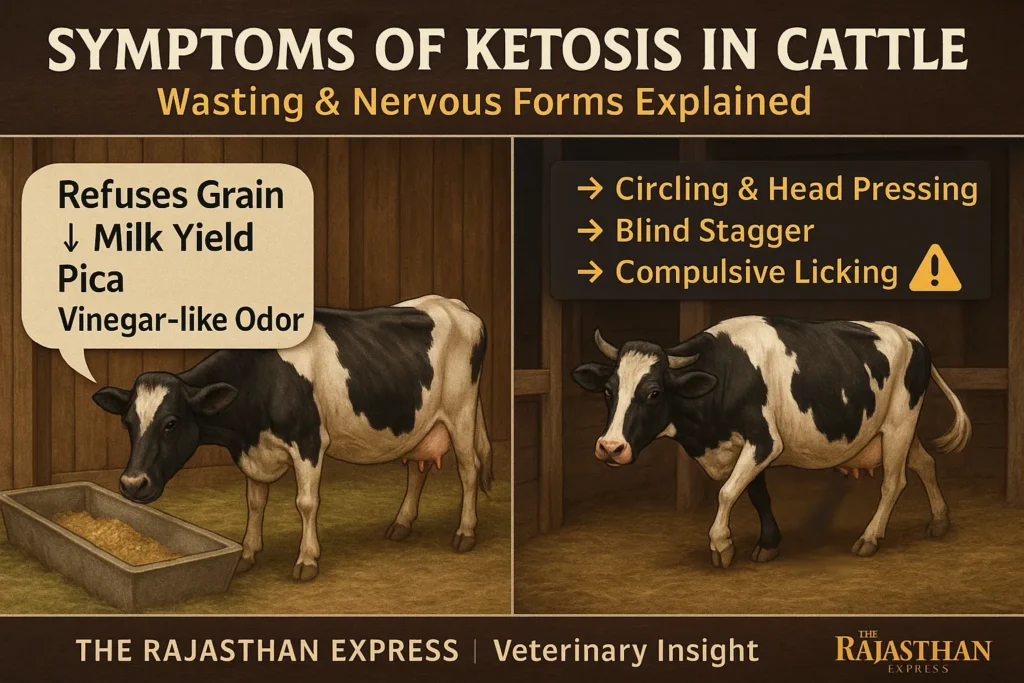

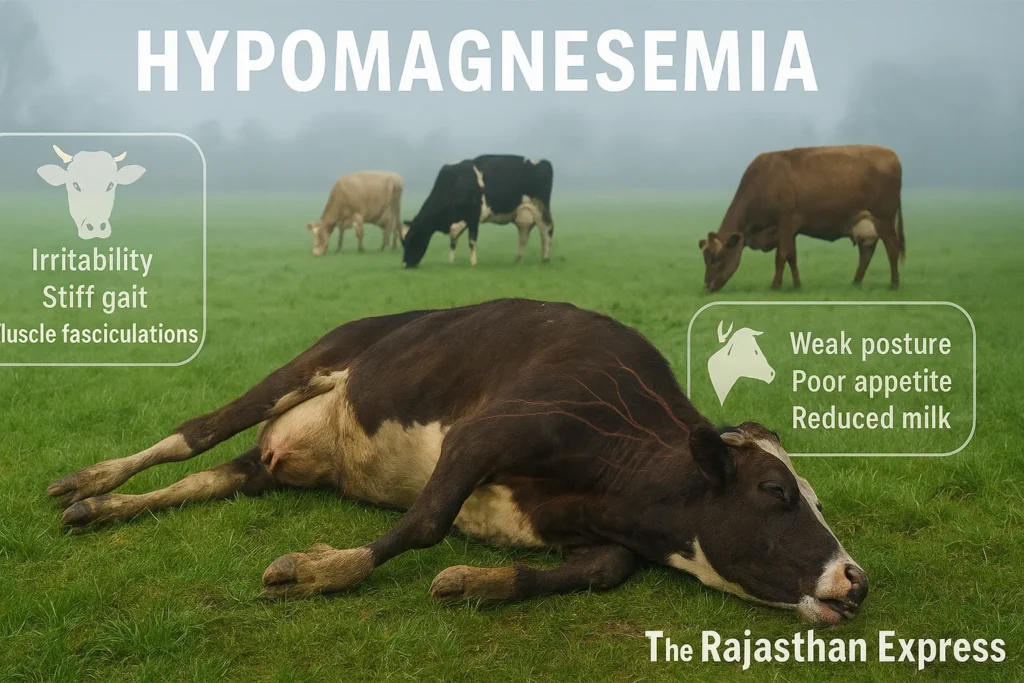

Grass Tetany Symptoms: Recognizing the Signs of Hypomagnesemia in Cattle

Clinical Manifestations and Neurological Effects of Hypomagnesemia

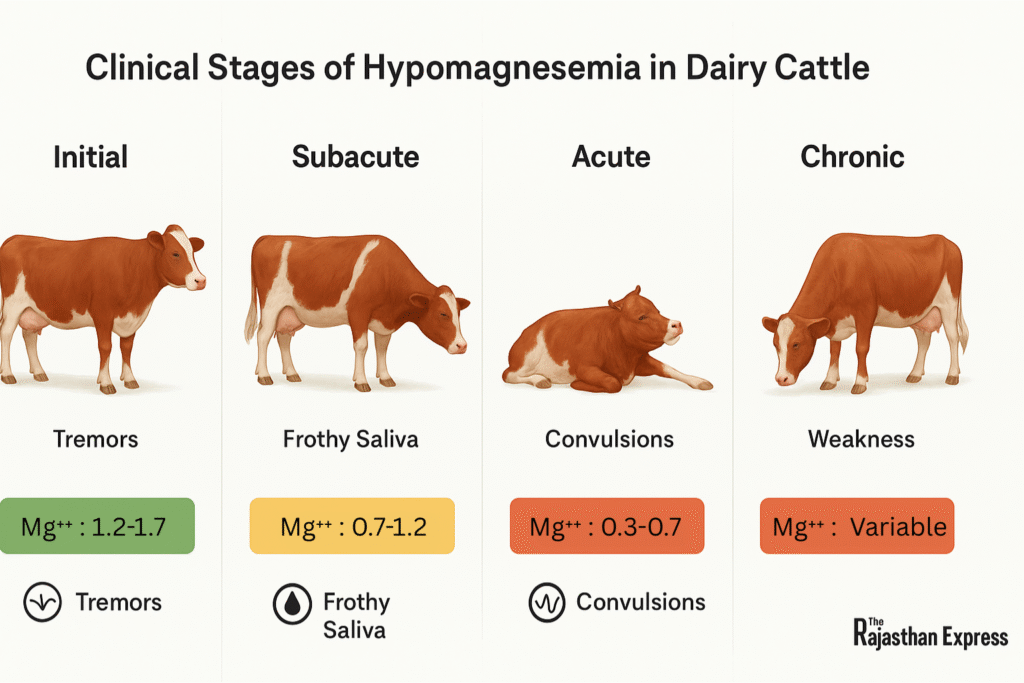

Hypomagnesemia, meaning low levels of magnesium in the blood, is a serious metabolic disorder whose primary clinical manifestation is tetany. Magnesium is an essential mineral for nerve and muscle function, and its deficiency causes neurological hyperexcitability. The severity of symptoms and their progression correlates with the degree of decrease in serum magnesium levels.

Symptoms and Clinical Progression of Grass Tetany

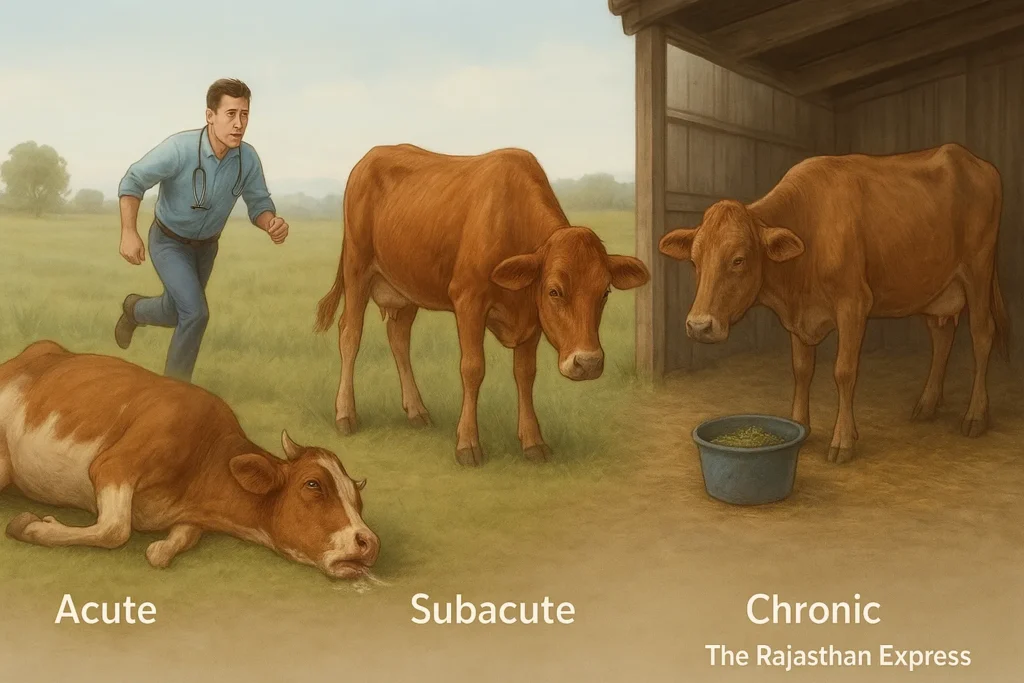

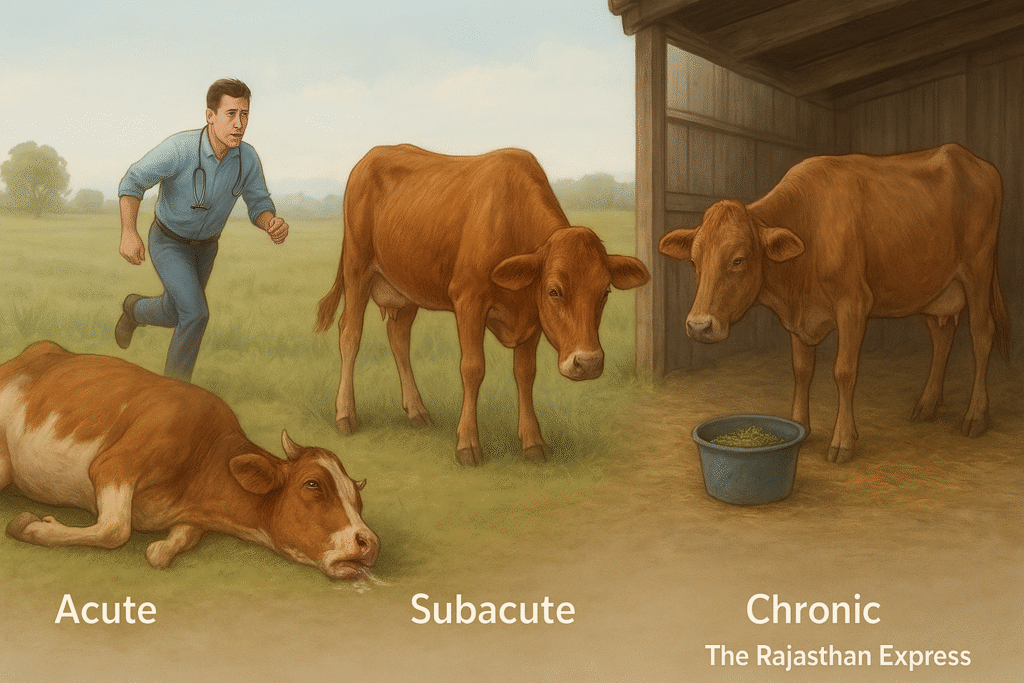

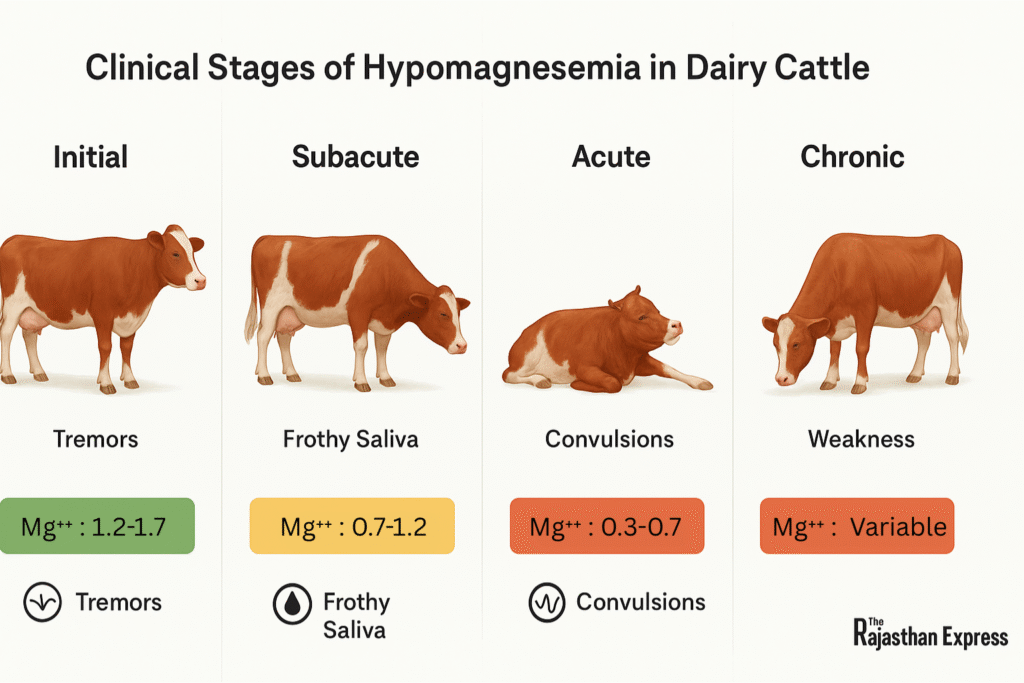

The clinical manifestations of tetany caused by hypomagnesemia progress through various stages, often starting with subtle and potentially overlooked signs.

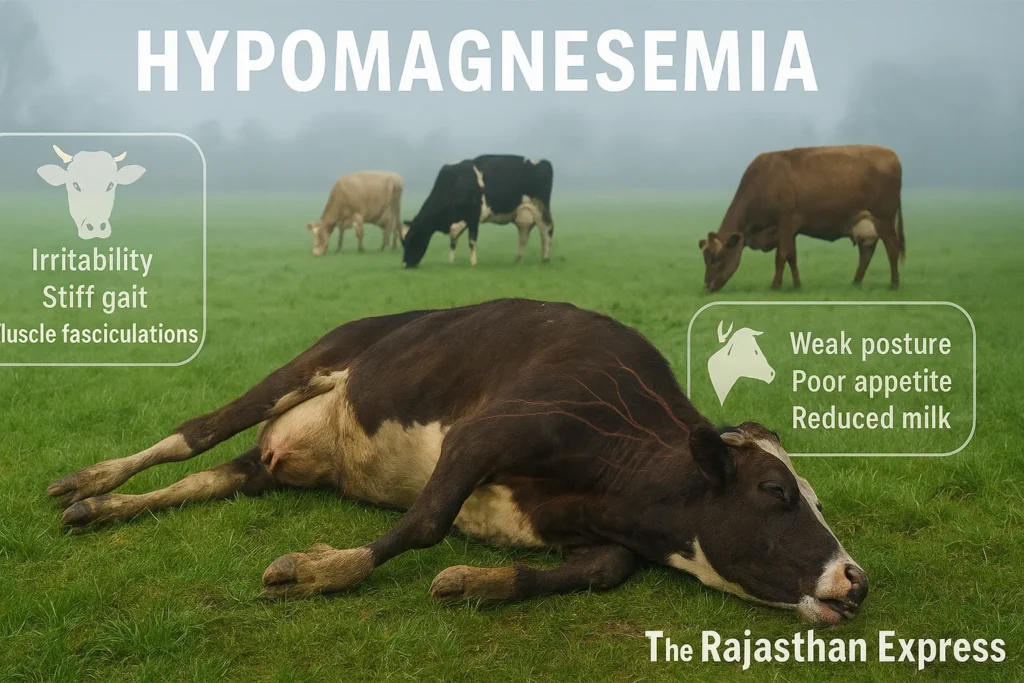

1. Initial Stage: Subtle Early Warnings

Initial symptoms include mild restlessness, irritability, loss of appetite (anorexia), and increased alertness (hypervigilance). These symptoms are indicators that the nervous system is already in an excited state. These subtle signs often transition into more apparent neuromuscular irritability, manifesting in these forms: muscle twitching and fasciculations (especially in the face, flanks, and shoulder areas), exaggerated responses to external stimuli, and an abnormal, stiff gait.

2. Acute Stage: Severe and Life-Threatening Signs

As the condition worsens, animals experience obvious tetanic convulsions (seizures), characterized by tonic-clonic contractions of the skeletal muscles. Affected animals may appear to be grazing normally and suddenly raise their heads, bellow loudly, and run blindly before collapsing. During a convulsion, animals typically display the following symptoms: paddling movements, chewing movements, frothy salivation, eyelid twitching, and nystagmus (involuntary eye movement). These symptoms may be accompanied by high fever (40–40.5°C) and increased pulse and respiratory rates. These acute neurological disturbances can recur at short intervals and often cause death within hours of the onset of symptoms if left untreated.

3. Subacute and Chronic Stage: Gradual Onset and Hidden Danger

In some cases, symptoms may appear gradually (over 3-4 days). These include: loss of appetite, a strange facial expression, abnormal limb movements, frequent urination and defecation, reduced rumination, constant muscle tremors, mild spasms in the hind legs and tail, an unsteady and staggering gait, and arching of the head backward (opisthotonos). Chronic hypomagnesemia often causes sudden death without any obvious warning, although some animals may only show vague symptoms like lethargy, poor physical development, and decreased milk production.

NOTE: Symptoms manifested in calves may differ from those in adult animals, including extreme sensitivity, head shaking, arching the body backward (opisthotonos), retraction of the eyelids, trembling limbs, and frothing at the mouth.

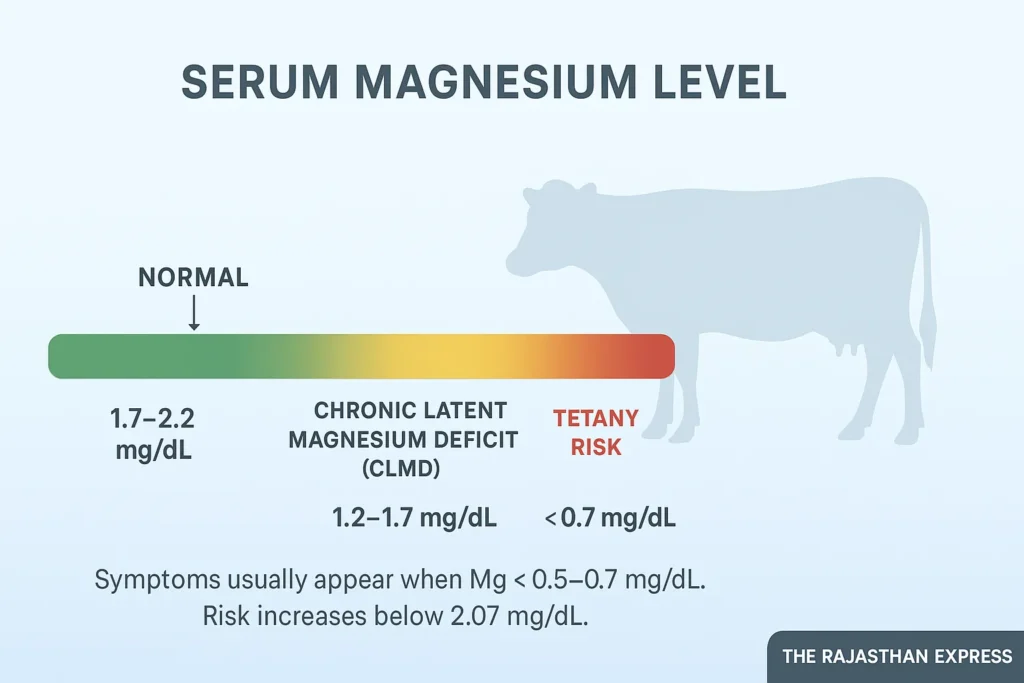

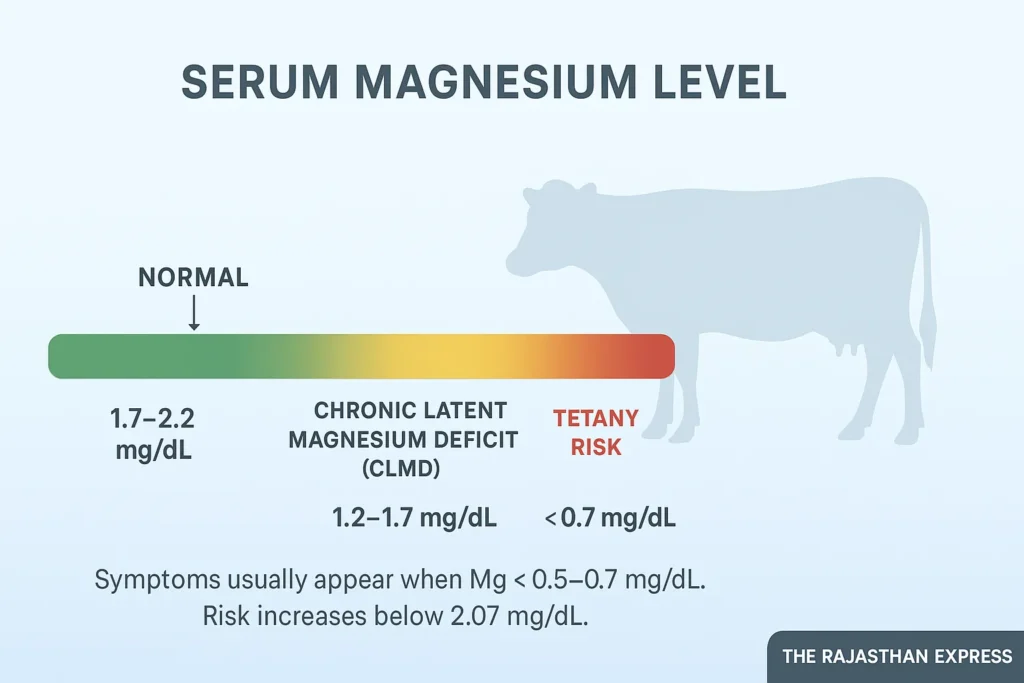

Critical Threshold Level for Clinical Signs

The normal serum magnesium concentration is 1.8–2.5 mg/dL. However, clinical symptoms typically appear only when levels fall below 0.5–0.7 mg/dL. Some studies suggest that a serum magnesium concentration of <0.85 mmol/L (≈2.07 mg/dL) should be considered a more appropriate diagnostic cut-off for hypomagnesemia, as values below this threshold are linked to an increased risk of several chronic diseases.

This discrepancy indicates that the traditional “normal” reference range may include animals experiencing Chronic Latent Magnesium Deficit (CLMD) — a condition in which magnesium levels are adequate to avoid overt clinical signs but remain insufficient to support long-term health.

CLMD refers to a state where blood magnesium values appear normal, but overall body magnesium stores are depleted. It is often diagnosed using a positive magnesium load test and reflects hidden, whole-body magnesium deficiency. CLMD is associated with symptoms such as weakness, muscle tremors, depression, and cardiac arrhythmias.

The Merck Veterinary Manual notes that CLMD is a significant cause of hypomagnesemia in multiple species, leading to systemic dysfunction. It further highlights that abnormal blood pressure is a common consequence of chronic magnesium deficiency.

The Pathophysiological Mechanism Behind the Symptoms

The neurological effects of magnesium deficiency arise from its central role:

- Neuromuscular Transmission: Magnesium acts as a natural calcium channel blocker. Magnesium deficiency leads to excessive calcium influx, causing hyperexcitability of neurons and muscle cells.

- Central Nervous System: Magnesium plays a protective role in the central nervous system by blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Magnesium deficiency can lead to uncontrolled activation of these receptors, causing neuronal degeneration and seizures.

- Neural Stability: Magnesium is essential for maintaining cell membrane stability. Its deficiency causes membrane instability, leading to the irregular discharge and propagation of nerve impulses, resulting in tetany and convulsions.

Summary of Hypomagnesemia Symptoms and Clinical Signs

The following table summarizes the clinical symptoms of hypomagnesemic tetany according to their progression:

| Summary of Hypomagnesemia Symptoms and Clinical Signs | ||

| Stage | Serum Mg⁺⁺ Level (mg/dL) | Key Clinical Signs |

|---|---|---|

| Initial | 1.2 – 1.7 | Restlessness, irritability, loss of appetite, muscle twitching. |

| Subacute | 0.7 – 1.2 | Muscle tremors (ears, face), staggering gait, chewing movements, frothy salivation, frequent urination. |

| Acute | < 0.7 | Generalized tetanic convulsions (tonic-clonic contractions), paddling, nystagmus, high fever (~40.5°C), rapid heart rate and respiration. |

| Chronic | Variable | Sudden death (without symptoms), lethargy, decreased production, poor growth. |

| 👉 In Calves: Extreme sensitivity, head shaking, opisthotonos (arched back), retracted eyelids, trembling limbs, frothing at the mouth. Clinical signs usually appear when serum magnesium falls below 0.3–0.7 mg/dL. | ||

Beyond Tetany: The Advanced Concepts and Long-Term Significance of Hypomagnesemia

The Broader Impact of Magnesium Deficiency in Cattle

The significance of hypomagnesemia is not limited to acute tetany. Research links it to several long-term risks:

1. Cardiac Risks and Electrical Instability

Magnesium is crucial for maintaining the heart’s electrical stability. Its deficiency increases the risk of cardiac arrhythmias, such as Torsades de Pointes, and other heart problems. This underscores why rapid IV treatment for Grass Tetany is so dangerous and must be administered with extreme caution to avoid fatal heart complications.

2. Link to Metabolic Syndrome and Overall Health

Hypomagnesemia is associated with insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). This indicates that a chronic, subclinical deficiency can undermine an animal’s overall metabolic health, making it more susceptible to other disorders and reducing its productivity and longevity.

3. Increased Hospitalization and Mortality Risk

Studies on human patients undergoing Peritoneal Dialysis have revealed that a low baseline serum magnesium level (<1.8 mg/dL) was associated with a higher risk of hospitalization and all-cause mortality, especially in patients with hypoalbuminemia. This serves as a crucial indicator of its severe impacts in veterinary medicine as well, suggesting that chronically low Mg levels can compromise an animal’s resilience and survival.

How is Hypomagnesemia Diagnosed? Differential Diagnosis for Grass Tetany

Diagnosing Grass Tetany adopts a multi-dimensional approach that combines field observation with laboratory confirmation. Veterinarians and farmers must act quickly based on clinical signs, but definitive tests are crucial for an accurate diagnosis.

Blood and Urine Tests: The Primary Diagnostic Tools

- Blood Tests: The cornerstone of diagnosis is measuring the magnesium level in the blood.

- Cattle: Normal serum magnesium level is between 1.8–2.4 mg/dL. Clinical hypomagnesemia is usually defined as a level below 1.2 mg/dL. Acute, fatal tetany is often associated with levels below 0.5–0.7 mg/dL.

- Sheep: Normal levels are higher (2.2–2.8 mg/dL), and the diagnostic level is also higher compared to cows.

- Check for Hypocalcemia: Calcium deficiency (serum Ca < 7.0-8.0 mg/dL) often occurs simultaneously and exacerbates the severity of symptoms. Assessing a combined deficiency is important.

- Urine Tests: An excellent, non-invasive method for herd-level monitoring.

- Normal urine Mg level: 1–20 mg/dL.

- A level below 1 mg/dL indicates a high risk of tetany and shows the immediate need for magnesium supplementation in the herd.

- Postmortem Diagnosis: In cases of sudden death, analyzing the magnesium concentration in the eyeball fluid (vitreous humor) is an invaluable tool.

- A level below 1.0 mg/dL within 24-48 hours of death is considered a potential cause of death due to hypomagnesemia.

- Cattle: Magnesium concentrations below 0.55 mg/dL within 48 hours postmortem are indicative of severe hypomagnesemia.

- Sheep: Magnesium concentrations below 0.65 mg/dL within 24 hours postmortem suggest severe hypomagnesemia.

- Vitreous humor magnesium concentrations closely parallel antemortem serum levels and remain stable for up to 48 hours postmortem, making it a reliable marker for diagnosing hypomagnesemia in ruminants.

Differential Diagnosis: Distinguishing Grass Tetany from Other Diseases

The symptoms of Grass Tetany resemble those of many other neurological and metabolic diseases. Accurate differential diagnosis is key to successful treatment. The following table helps differentiate between major diseases causing similar symptoms in ruminants:

| Differential Diagnosis: Distinguishing Grass Tetany from Other Diseases | ||||

| Disorder | Primary Deficiency | Common Onset | Key Clinical Signs | Key Diagnostic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypomagnesemic Tetany | Magnesium | Pasture season (Spring/Autumn) | Muscle twitching/tremors, tetanic spasms, blind running, frothing, nystagmus | Low serum Mg (<1.2 mg/dL), often with hypocalcemia; urine Mg <1 mg/dL |

| Milk Fever | Calcium | Immediately after calving or within 48 and 72 hours | Recumbency, inability to stand, cold extremities, S-shaped neck, coma | Low serum Ca (<6.5 mg/dL); rapid, dramatic response to Ca treatment |

| Postpartum Hemoglobinuria | Phosphorus | A few weeks after calving | Dark red-brown urine, severe weakness, pale mucous membranes, rapid breathing | Low serum P, hemoglobinuria, anemia, hemoglobinemia |

| Ketosis | Energy (Glucose) | Early lactation | Weight loss, sweet/acetone breath, nervous signs (irregular licking, compulsive chewing) | Ketonuria (urine ketones), hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) |

| Rabies | Lyssa Virus | Any time (after virus exposure) | Aggression, paralysis, dysphagia, strange vocalizations, history of dog bite | No specific blood/urine changes; diagnosis by microscopic exam of brain tissue |

| Lead Poisoning | — | Any time (contaminated feed/water) | Blindness, convulsions, aggression, foaming at mouth, abdominal pain | High lead levels in blood/liver; anemia (nucleated RBCs) |

| Nitrate/Nitrite Toxicity | — | After eating nitrate-rich feed | Chocolate-brown/blue mucous membranes, labored breathing, weakness, sudden death | Chocolate-brown blood (methemoglobinemia), high nitrate levels in feed/blood |

| Use clinical signs + confirmatory tests to distinguish tetany from other acute neurologic/metabolic disorders. | ||||

Advanced Diagnostic Concepts

- Ionized vs. Total Magnesium: Magnesium in blood is found in three forms—ionized (active, ~55–60%), protein-bound (~30%), and complexed (~10%). Traditional testing methods often only measure total magnesium. However, ionized magnesium (iMg²⁺) is a more accurate indicator of the body’s actual physiological state, especially when protein levels are abnormal (e.g., hypoalbuminemia). Therefore, measuring iMg²⁺ aids in more precise diagnosis.

- Electrocardiography (ECG) Changes: Severe hypomagnesemia affects the heart’s electrical activity. ECG may show life-threatening arrhythmias like Torsades de Pointes, prolonged QT interval, and flattened T-waves. These changes become even more pronounced with concurrent hypocalcemia, as the two conditions often occur together.

- Cellular Level Effects: Diagnosis should not be limited to serum levels. Chronic Latent Magnesium Deficit (CLMD) is a condition where, despite serum levels being at the lower end of the “normal range” (e.g., 1.8–2.0 mg/dL), a magnesium deficiency already exists within the cells. This makes the animal more susceptible to other diseases (e.g., ketosis, mastitis), which can negatively impact the herd’s overall productivity and health.

In conclusion, effective diagnosis of hypomagnesemic tetany relies on a combination of clinical suspicion, laboratory confirmation (including urine and vitreous humor analysis), and careful elimination of other important diseases. Understanding advanced concepts like ionized magnesium and chronic latent deficit can take disease prevention and management strategy to a new level.

Grass Tetany Treatment and Prevention: A Complete Management Guide

Effective Treatment Protocols for Hypomagnesemic Tetany

Hypomagnesemic tetany, often also known as Lactation Tetany or Grass Tetany, is a serious medical emergency in animals. This condition requires immediate treatment; otherwise, the animal may die.

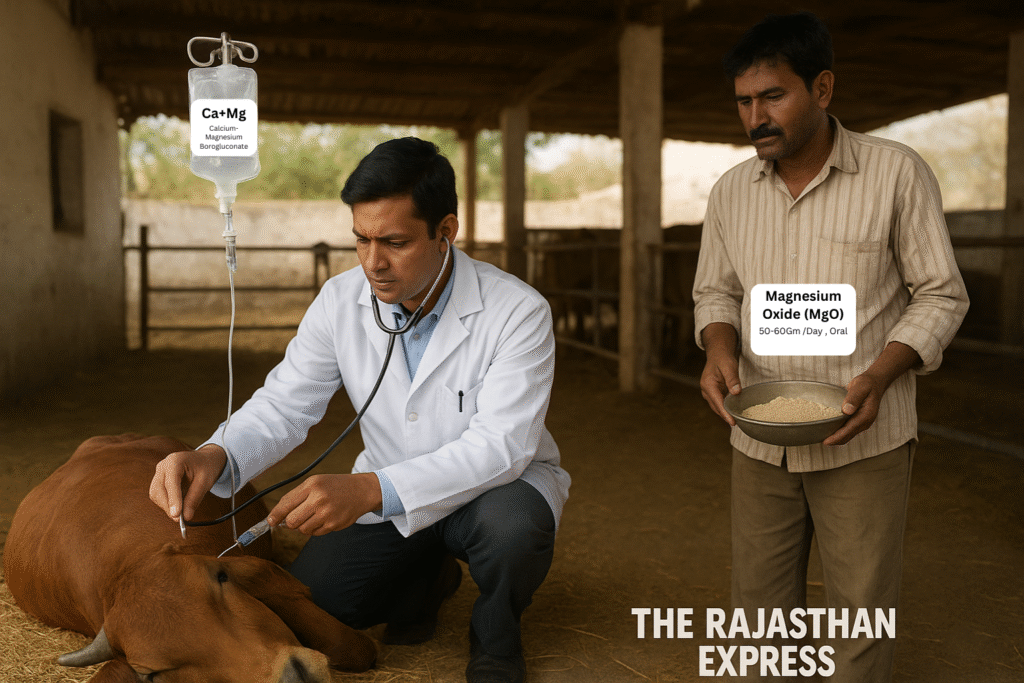

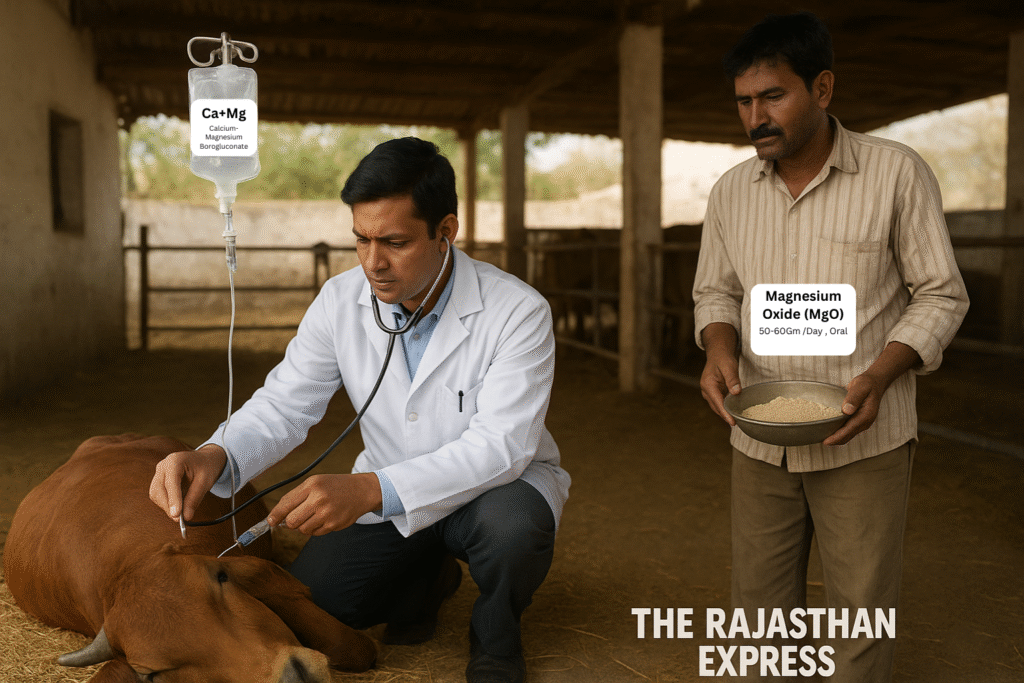

Immediate Emergency Treatment for Grass Tetany

The first step in the acute management of tetany involves administering specific injections of calcium and magnesium. The standard treatment approach is:

Standard IV Therapy Protocol

A common protocol is to administer a mixture of 40% calcium borogluconate (approx. 400 mL) and 25% magnesium sulfate (approx. 50 mL) via the IV route.

Alternatively, a prepared calcium-magnesium borogluconate solution (which typically contains 1.86% calcium borogluconate, 5% magnesium hypophosphite, and 20% dextrose) can be used.

- Large animals (Cow): 400–500 mL, administered slowly IV.

- Small animals (Sheep/Goat): 50–100 mL, administered slowly IV.

Critical Precautions During IV Administration

- Extremely Slow Infusion: The IV injection should be given over at least 10-15 minutes. Rapid IV injection can cause a drop in heart rate (bradycardia), irregular heartbeat (arrhythmias), and sudden death.

- Constant Heart Monitoring: The animal’s heart rate should be continuously monitored during administration. If the heart rate becomes irregular or decreases significantly, the injection should be stopped immediately and then restarted at a slower rate.

Adjunctive Therapy for Seizure Control

In animals with severe convulsions, sedative drugs may be necessary. Sedatives like Xylazine (0.05 mg/kg, IM) can help control seizures and calm the animal, allowing for the safe administration of IV treatment.

Follow-Up Care and Oral Supplementation

The effect of IV treatment is short-lived. Follow-up treatment is essential to stabilize magnesium levels and prevent relapse.

- Subcutaneous (SC) Injection: After acute treatment, 120-400 mL of 25% magnesium sulfate can be given SC. This creates a slow-absorbing depot that maintains blood magnesium levels for several hours.

- Oral Supplementation: Once the animal has recovered, oral supplementation should be initiated.

- Magnesium Oxide (MgO) is the most commonly used source, with a recommended dosage of 50-60 grams per cow per day. It can be mixed into grain or feed.

- In the days following treatment, 100–200 g of magnesium sulfate should be mixed into the feed daily for 3–5 days.

Treatment Protocol for Calves

- Administer 100 mL of 10% magnesium sulfate slowly IV.

- Subsequently, Magnesium Oxide (MgO) should be given orally at a rate of 10 g/day.

Important Considerations for Recovery

Recovery from this disease takes longer than from simple milk fever because restoring magnesium levels in the brain and spinal fluid is delayed.

The recovering animal should not be stressed excessively and should be removed from the pasture where there is a risk of this disease.

Clinical Recovery, Aftercare, and Long-Term Management

Recovery from hypomagnesemic tetany (Grass Tetany) is significantly slower than from common milk fever. The main reason is that it takes more time for magnesium levels to normalize after crossing the blood-brain barrier. This is why, even after treatment, the animal may remain weak, lethargic, and unsteady on its feet for several hours.

Stress management during this time is extremely important. The recovering animal should be protected from any kind of excessive disturbance or stress. Keep it in a calm, shaded, and well-ventilated place. Most importantly, do not return it to the same pasture where there was a risk of this disease.

Prevention and Control of Grass Tetany in Cattle

The best way to prevent this fatal disease is through proactive and intelligent management.

- Pasture Management: Move at-risk animals (e.g., high-producing dairy cows) to safe pastures during the Grass Tetany season (winter). Graze them in areas where the grass has a balanced nutrient profile.

- Supplementation: Feed lactating cows at least 60 grams of Magnesium Oxide (MgO) or magnesium chloride daily. This can be mixed into feed or provided as a special mineral mixture.

Measures for Preventing Hypomagnesemia

| Measures for Preventing Hypomagnesemia | ||

| Measure | Description | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Supplementation | 50–60 grams of Magnesium Oxide (MgO) or Magnesium Chloride per cow per day, mixed into grain or TMR (Total Mixed Ration). | The most common and effective method. Maintains consistent blood Mg levels. |

| Pasture Management | Preventing animals from grazing on young, rapidly growing pastures during high-risk seasons (spring/autumn). Feeding them dry fodder or silage. | Reduces the K:Mg ratio and improves Mg absorption. |

| Mineral Licks | Providing Mg-containing mineral blocks or salt licks. | Animals can self-regulate, but intake control is less reliable. |

| Grain Dressing | Treating grains with a 2% Magnesium Oxide solution. | An effective way to ensure consumption. |

| Slow-Release Boluses | High-Mg boluses placed in the animal’s rumen. | Provide a continuous release of Mg for several weeks, especially during high-risk periods. |

| Preventive strategies should be tailored to season, pasture type, and animal production stage for maximum effectiveness. | ||

Advanced Concept: The Potassium-Magnesium Interaction

Understanding the relationship between potassium and magnesium is crucial to understanding the risk of Grass Tetany. Young, green, rapidly growing grass in winter has very high levels of potassium (K) and low levels of magnesium (Mg).

This high potassium directly impedes the absorption of magnesium in the animal’s rumen (first stomach). Consequently, despite consuming plenty of green fodder, the animal becomes deficient in magnesium. This is why proper pasture management and regular supplementation are the only solutions to this problem.

Conclusion and Sample Collection for Diagnosis

In summary, the successful management of hypomagnesemic tetany requires a comprehensive strategy:

- Immediate Treatment: Immediate IV treatment with veterinary assistance for acute symptoms.

- Follow-Up Care: SC injections or oral medications to prevent relapse.

- Long-Term Prevention: Adopting strict preventive measures, such as providing magnesium supplements and managing pastures.

Sample Collection for Definitive Diagnosis

For accurate diagnosis, veterinarians may collect the following samples:

- Blood: To measure serum Magnesium, Calcium, and Potassium levels.

- Urine: To assess urinary Magnesium concentration (a level <1 mg/dL indicates high risk).

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF): In rare cases, to measure CSF Mg levels, which are critically low during tetany.

“Grass Tetany (Hypomagnesemia) is a deadly metabolic disorder in cattle caused by magnesium deficiency. Learn to spot early symptoms like muscle twitching and agitation, administer emergency IV calcium-magnesium solutions, and implement preventive strategies like dietary supplementation and pasture management to protect your herd.”

THE RAJASTHAN EXPRESS