Foot Rot Disease in Animals: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

“While monsoons accelerate foot rot spread, our 2024 Rajasthan case study proved hygiene negligence caused 68% of outbreaks—not rainfall. Farmers using dry-bedding protocols saw 92% lower infection rates despite heavy rains.”

Dr. Vikram Singh, Livestock Pathologist

Foot rot disease is a bacterial infection that primarily affects cloven-hoofed animals such as cows, buffaloes, sheep, goats, pigs, and camels. Among these, it is most commonly observed in cows, buffaloes, sheep, and goats.

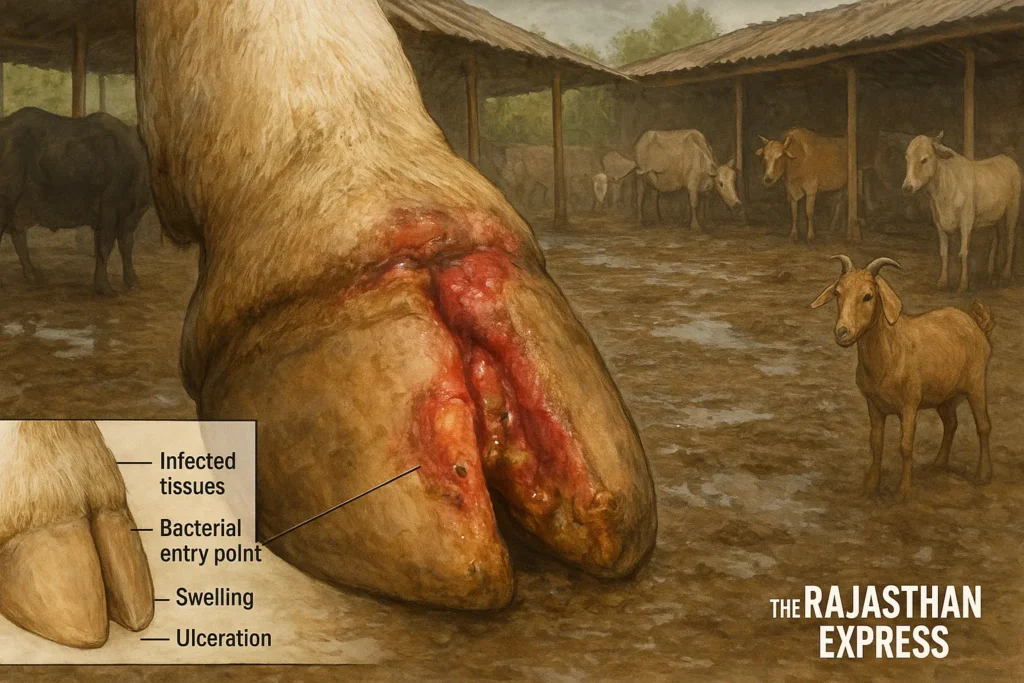

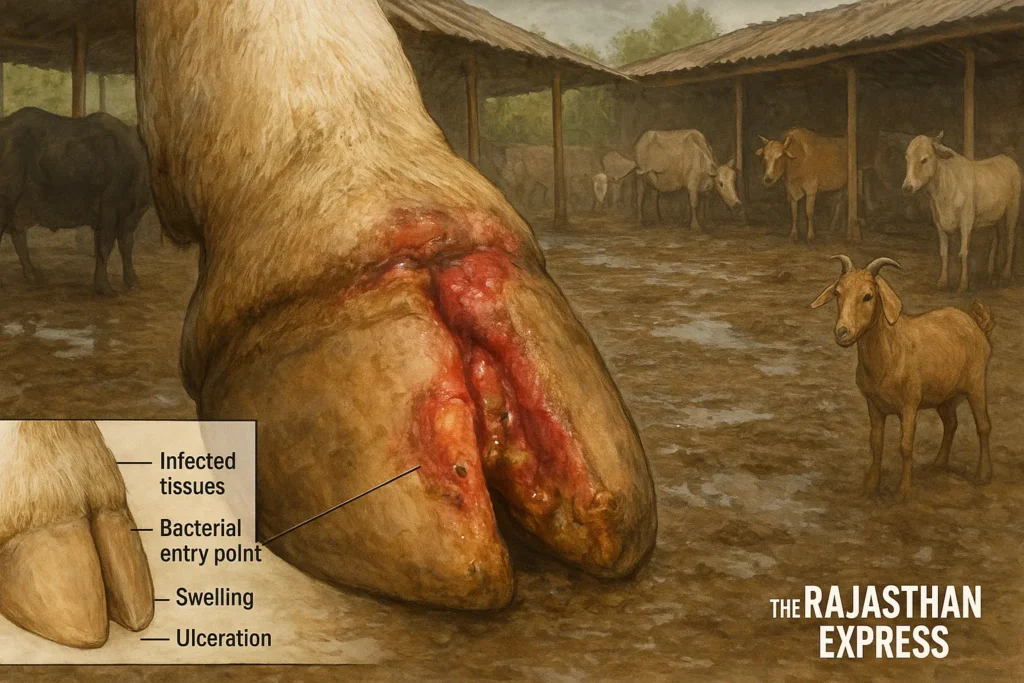

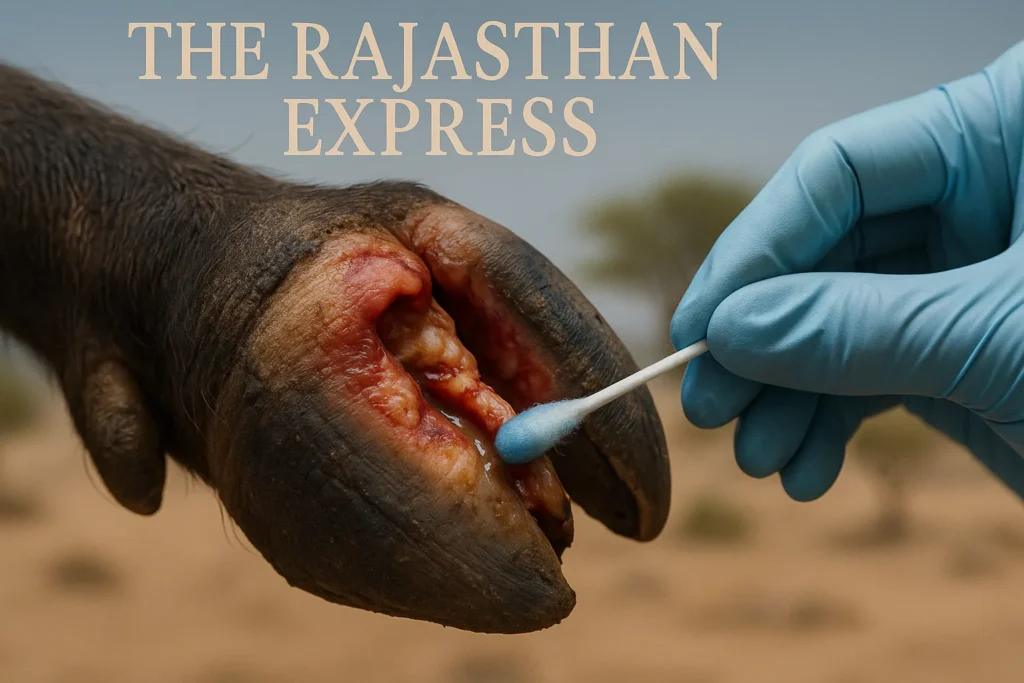

In this disease, wounds, swelling, and ulcers develop between the hooves. If left untreated for a long period, necrosis (tissue death) can occur in the hoof cells. This is a contagious disease characterized by swelling, decay, and ulcer formation in the interdigital space, coronary band, and dorsal limbs, leading to lameness.

In rural areas, it is also known as “Khura Pakna” (hoof decay).

Foot Rot (Interdigital Necrobacillosis) in Cloven-Hoofed Animals

| Alternative Names | Khura Pakna, Foul-in-the-Foot, Infectious Pododermatitis |

|---|---|

| Affected Species | Cows, Buffaloes, Sheep, Goats; occasionally Pigs, Camels |

| Etiological Agents |

|

| Pathogenesis | Skin trauma or prolonged moisture → bacterial invasion → leucocidal exotoxins (F. necrophorum) and proteases (B. melaninogenicus, D. nodosus) → necrosis, ulcers, swelling, potential progression to joints/septic arthritis . |

| Prevalence & Risk Factors |

|

| Clinical Signs |

|

| Diagnosis | Based on characteristic lesions and odor; severe interdigital fissures; differential diagnosis includes interdigital dermatitis, sole abscesses, fractures, septic arthritis. |

| Treatment |

|

| Foot Baths & Disinfection |

|

| Trace Mineral & Iodine Supplementation |

|

| Vaccination | Vaccine against D. nodosus (e.g., Footvax) shows 60–80% efficacy in sheep; in cattle, vaccines may reduce case numbers but are not standalone preventive measures . |

| Environmental & Management Prevention |

|

| Economic Impact | Leads to reduced production, weight gain, milk output; severe cases may require culling or costly treatment. |

| Sources: K-State Vet College; USDA/Extension Services (Oklahoma State, Penn State, LSU); Merck Vet Manual; DVM360; The Rajasthan Express | |

Foot rot disease is more common in animals that spend prolonged periods in dirty water, manure, and urine, especially when proper cleanliness is not maintained in the barn. The disease spreads rapidly during the monsoon season due to continuous moisture, which makes it difficult to keep the barn dry.

When hooves remain wet and dirty for extended periods, the skin becomes weak. Cracks in the skin allow bacteria to enter the body, causing infection.

Causes of Foot Rot Disease in Cattle, Sheep, and Other Animals

The main bacterial agents causing foot rot disease include:

- Fusobacterium necrophorum

- Dichelobacter nodosus (especially in sheep)

- Bacteroides melaninogenicus (more common in cows)

These are all Gram-negative, anaerobic bacteria (able to survive without oxygen).

The disease occurs more often in animals whose hooves are constantly exposed to dirty water, manure, and urine. This weakens the skin and tissues around the hooves, allowing bacteria like Fusobacterium necrophorum to penetrate and cause infection.

- Fusobacterium necrophorum is naturally found in the digestive tract of ruminants and can survive in soil for up to 10 months. It produces a leucocidal exotoxin that reduces the ability of white blood cells to fight infection, leading to suppurative necrosis (pus-filled tissue destruction).

- Bacteroides melaninogenicus produces proteases that damage subcutaneous tissues and tendons.

- Dichelobacter nodosus, common in sheep, can survive in the environment for about two weeks and produces enzymes that destroy connective tissue between the hoof horn and flesh, allowing deeper bacterial invasion.

If untreated, the infection can reach the joints, causing septic arthritis. The disease is seasonal, spreading more during the rainy season. Cuts, abrasions, or puncture wounds also provide entry points for the bacteria.

Foot Rot Disease Symptoms

- Visible lameness due to wounds between the hooves — the most prominent sign.

- Mild fever, reduced appetite, and decreased milk production due to lameness.

- Redness, swelling, and pain in the interdigital space, causing the animal to repeatedly lift its foot.

- In sheep and goats, the outer horny covering of the hoof may peel off if untreated.

- Difficulty walking is an early indicator.

- Difference from FMD: Foot rot affects only the hooves, whereas FMD (Foot-and-Mouth Disease) affects both mouth and hooves.

- Separation of horny hoof tissue and a distinct foul odor help identify the disease.

- Animals may stamp their feet due to pain or be unable to walk.

- Sometimes the animal walks on only two legs.

- One or multiple legs can be affected simultaneously.

- Spreading of toes and dewclaws is also characteristic.

How Foot Rot Disease Spreads (Mode of Transmission)

- Constantly wet, muddy environments and uneven ground that cause skin cracks.

- Tick bites or entry of Strongyloides papillosus larvae into the skin.

- Warm and humid conditions (20–25°C), soil, manure, filth, and wet bedding act as common sources of infection.

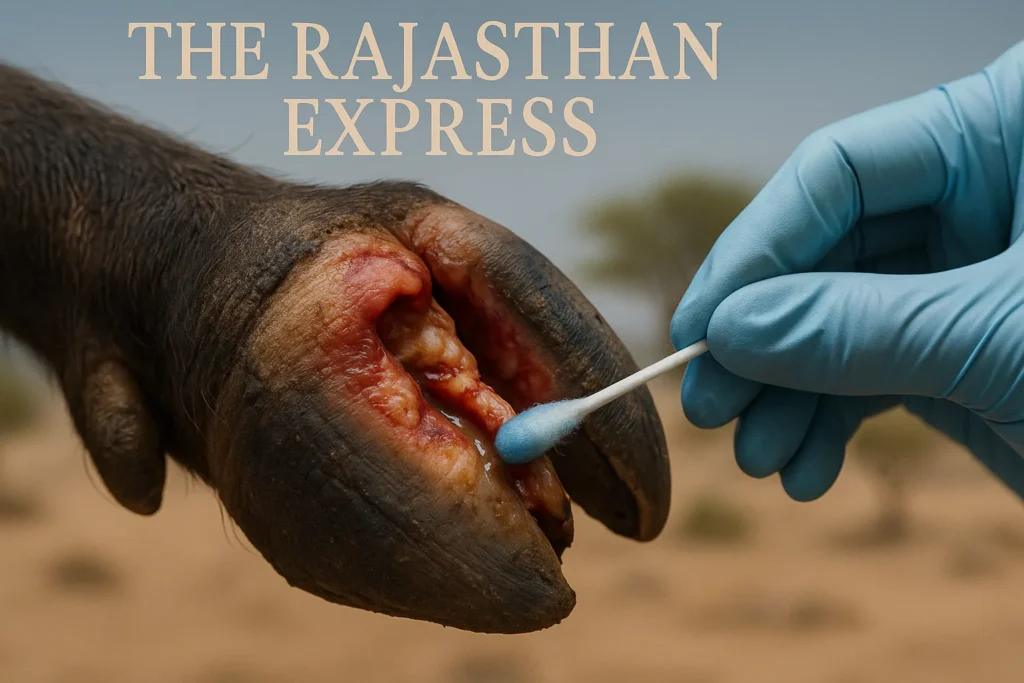

Diagnosis of Foot Rot Disease in Animals

- Diagnosis is primarily based on symptoms,

- Particularly interdigital fissures (skin cracks) and a characteristic foul odor.

Management of Foot Rot in Cattle, Sheep, and Goats

- Keep infected animals in a dry, clean, level area with sand or sandy soil to reduce moisture.

- Isolate infected animals from healthy ones to prevent spread.

- Use foot baths with 10% copper sulfate, 10% zinc sulfate, 4% KMnO4 or antiseptics like povidone-iodine ,.

- Trim hooves at least twice a year to prevent dirt accumulation and infection.

- Disinfect barns regularly with phenyl, bleaching powder, or iodine solution to prevent reinfection.

- Before the monsoon, take measures to prevent mud and moisture buildup in animal housing.

Foot Rot in Cattle and Sheep Treatment

Foot rot is caused by Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria:

- Fusobacterium necrophorum

- Dichelobacter nodosus (especially in sheep)

- Bacteroides melaninogenicus (in cattle)

Treatment steps:

- Clean hoof wounds thoroughly with antiseptic solutions (iodine or chlorhexidine) to prevent bacterial spread.

- Antibiotics:

- Oxytetracycline – A broad-spectrum antibiotic effective against Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria; widely used for foot rot.

- Penicillin + Streptomycin combination – Works synergistically for better results, as foot rot is usually a polymicrobial infection.

- In severe cases, surgical hoof trimming along with a foot bath is recommended.

Vaccination for Foot Rot Disease

- A special vaccine is available for controlling foot rot in sheep caused by Dichelobacter nodosus.

- Commonly known as Footvax, it helps protect sheep from the disease and reduces economic losses.

Learn about foot rot disease in cattle, sheep, and goats – causes, symptoms, treatment, and prevention tips. Expert guide on managing and controlling hoof infections.

THE RAJASTHAN EXPRESS